"La Dolce Vita" (The Sweet Life) is a provocative film, filled with humor and pain, joy and despair, spectacle and emptiness. It's generally regarded as one of Fellini's masterpieces, and its images will stay with me a long time.

I can't say I understand completely what Fellini was trying to convey. It was filmed in 1961, which in many ways was a completely different era, but it still has resonance 45 years later and the things that touched Fellini then echo through to today. The cult of celebrity fed by the scandal sheets is still with us, and the photographer character Paparazzo inspired the term that's used to this day for the intrusive and omnipresent media. The place of faith and spirituality in our modern society is a question with which we're all struggling in a time where religious fanaticism of all guises has captured public debate. And the search for love, connection, and meaning are universal human concerns that will always bedevil us.

Marcello Mastroianni plays Marcello Rubini, a gossip journalist who in many ways is a stand-in for Fellini himself -- observer, recorder and participant in the farcical parade of events that make up modern life's rich pageant.

Morality and spirituality in modern society

I think it's easy to look at Marcello's behavior in the film and see it simply as excessive, indulgent and decadent. But there is a darkness, a despair underlying everything he does, and I think that's where the strength of the movie lies. There is a lot of discussion in the film about individual freedom and choice. In modern society where the institutions that once guided those choices have been undermined or lost relevance the burden of that freedom can become overwhelming, provoking an urge to escape the need to choose completely.

The role of religion in society is still a hot topic, with fundamentalists calling for the protection of the "institution of marriage" and a general criticism of public policy that is not guided by religious principles (interestingly enough a call that comes from Christian fanatics here and Islamic ones in the Middle East). But this is a simplistic argument that argues for a return to an idealized past where "morality" held sway. The reality is that for many, religion lost relevance because it could not or would not adapt itself to the changed social conditions. Many religious orthodoxies were organized based on a feudal past and don't speak to the dilemmas of a post-industrial, global society.

There are two scenes in the movie that specifically portray this conflict between traditional religion and modernism. The film opens with a shot of two helicopters flying through the ruins of Rome. One carries a golden statue of Jesus; his arms outstretched as if to bless the city. Their destination is the Vatican, but Marcello takes a detour to flirt with some attractive sunbathers he spots along the way. The Jesus figure attracts the attention of the passers by below not because of his religious symbolism, which has fallen into decay like the Roman forum, but because of the mere spectacle of a flying statue.

Later, Marcello travels to the country to do a story on two children who claim to have seen the Virgin Mary by a tree. Paparazzo and his gaggle of photographers are on the scene and they direct the relatives of the children in various staged poses. Radio recorders, film lights and cameras also attempt to document the events, all the while shaping them into their own fictions. A priest questions the honesty of the children, guessing it's a crass attempt to make money off the Virgin. A combination of the curious well-to-do and the faithful poor descends on the area. This tension between the ancient and the modern, the spiritual and the commercial, the sacred and the profane, ends in confusion, doubt and death.

I'm not trying to say there's no place for spirituality and morality in modern society. On the contrary, I think the need is even greater and the challenge is for religions to find a way to bring hope to those who can only see despair in the choices presented by the modern world. That void is best demonstrated by the character of Steiner, Marcello's friend. At his party, we see Steiner as a loving father who fawns over his two children. Marcello envies him, his house, his family, and his friends, but these outer trappings mask the same unhappiness and restlessness. He warns Marcello away from a life "where everything is calculated, everything is perfect." He describes his fear of peace: "To me it seems that it's only an outer shell and that hell is hiding behind it." He worries about his children's future, where the end of the world can be announced with a phone call, and tragically he takes both their lives before committing suicide.

Love as sanctuary and salvation

In the absence of religion, I think the natural tendency is to seek spiritual salvation in romantic love. Marcello proclaims his love for several women in the film, and you don't get the sense that he is in anyway lying to them. Granted, his understanding of what love means may differ greatly from the women he pursues, and the end results may prove less than satisfying, but I think he genuinely feels love in some way each time; maybe it is a love of beauty in various forms or of the feminine in general; maybe it is just living in the moment. In a world where lasting, deep connections have become more difficult to find, the significance of any connection, no matter how brief or superficial, becomes heightened.

Marcello's first romantic encounter is with Maddalena played by Anouk Aimee. I think her name is no coincidence, recalling Mary Magdalene from the New Testament, a link that is reinforced by the fact that the two make love in the bed of a prostitute. She tells Marcello "only love gives me strength," but for her too the connections are fleeting and even harmful -- she wears sun glasses to conceal a black eye. Later in the film, Marcello meets her in a castle and they hold a conversation while in separate rooms, their voices traveling through the walls via a hole in the base of a statue. Maddalena wants to marry Marcello, but she also wants to be a "whore," and she can't choose between the two impulses. Marcello never characterizes himself in the same way, but his conflict is exactly that as we see in his relationship with Emma.

Emma (Yvonne Furneaux) is Marcello's failed try at a longer-term relationship. She's clinging, jealous and maternal toward Marcello, and her possessiveness drives him away. Despite this, he repeatedly returns to her -- maybe out of love, maybe out of obligation, maybe both. She attempts suicide after his night out with Maddalena. Tellingly, while she's recovering from this, he phones Maddalena from the hospital -- a call that goes unanswered. Marcello's friend Steiner advises her, "The day you understand that you love Marcello more than he does you'll be happy." The fact that she can't possess him, can't control him tears her apart, but just as Marcello keeps returning to her, she keeps waiting for him to do so. In one scene toward the end of the film, he abandons her in the middle of nowhere after a fight, driving off without her. She paces the road through the night knowing he'll come back for her, and he does at day break.

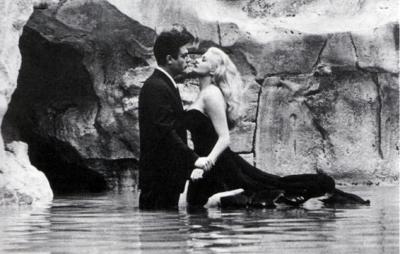

Sylvia (Anita Ekburg) is a woman purely from the realm of fantasy; a blonde, buxom Swedish movie starlet. As Marcello says, she has the beauty of a big doll. In the interview scene, she says that there are 3 things she likes most in life: "love, love and love." But for her, it's all make believe. Marcello chases her up the steps at the Vatican, a vision leading him to some false salvation. Dancing with her that night, he tells her that she is the "first woman of the first day of creation." She has a child-like innocence, as through the course of their shared night she bays at dogs along the side of a road, plays with a stray cat, and wades into the Trevi fountain. Marcello pursues her throughout, but he can't have her to himself and he gets a punch in the stomach from her jealous boyfriend as the reward for his efforts.

I think it's the hope of finding transcendence through love that drives Marcello's restless pursuit of women. It's a romanticized notion of finding salvation through love in its most innocent and spiritual form. I think the girl Paula, who he meets while trying to write at a beach-side restaurant, is symbolic of this. He describes her as an "Umbrian angel", and she appears again at the end of the film, seemingly offering him a last chance at changing the path he's on. It might be a false association, but it reminds me of Dante's Vita Nuova and the figure of Beatrice who from heaven leads him to a more spiritual life.

It's the repeated failures in his search for fulfillment through love and art that lead Marcello to the debased state we witness at the end of the film. At the final party, he's drunk, bitter and abusive. Having given up his ambition toward literature, ridiculed as an "intellectual", reduced to a publicist, he makes no pretense at finding love.

Broken conversations

A motif of cut off and obscured voices runs throughout the film. In the first scene, Marcello has difficulty communicating with the sunbathers because of the helicopter's din. Marcello's conversation with Maddalena in the castle ends with him desperately searching for her after she falls silent while in the embrace of another man. One friend describes Steiner as a Gothic Spire "so tall that you can't hear any more voices up there."

At the film's end, at the beach after a monstrous fish that "insists on looking" is brought ashore, Marcello tries to understand what the cherubic Paula, her voice drowned out by wind and waves, is trying to tell him. She appears to be asking him to walk with her, but finally, fatalistically, he gives up, waves goodbye and joins the other party goers leaving the beach. Paula's smiling face fills the final frames, and her gaze turns from Marcello to the camera, drawing us into the conversation.

No comments:

Post a Comment